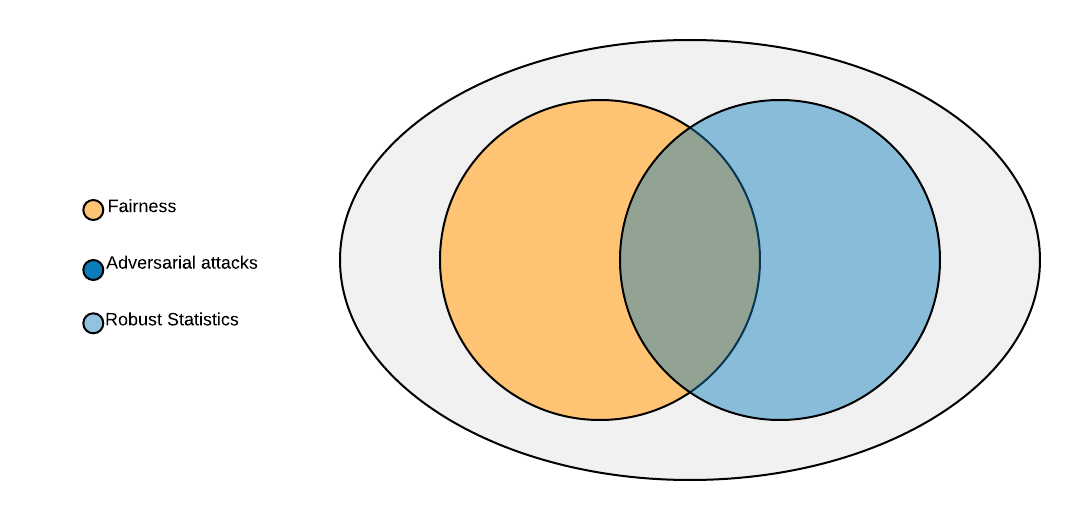

This article is written as an attempt to provide an intuitive explanation of the connectedness between fairness and adversarial attacks. The concept of fairness and adversarial attacks keeps evolving, and as such, it is impossible to cover in one blog post.

**Note: This should not be taken as a serious scientific endeavor. The work displayed here is for illustrative purposes only.**

We will discuss fairness in detail and then take a dive into adversarial attacks and conclude by finding the connection between fairness and adversarial attacks. Following the hacker’s path, it is desirable to learn by connecting the dots between seemingly related concepts. It is critical to understand that many aspects of fairness can only be fixed by the legislature. Our goal is to find how both concepts are connected, albeit with analogies, informal proofs, and philosophies.

### Fairness

Real-world data may be biased in ways that can be difficult to anticipate. For example, most resumes are biased towards successful accomplishments, whereas the real world is plagued with ups and downs. Society reinforces this bias by rewarding success and penalizing failure. Machine learning has the potential to worsen social inequalities when misused. This problem can happen due to algorithm bias, data imbalance, and data irregularities. Fairness is an attempt to solve the problem by trying to explain the blind spot in the model as described in [blog](https://jeremykun.com/2015/10/19/one-definition-of-algorithmic-fairness-statistical-parity/). An unacceptable approach to ensuring fairness is to remove racial and demographic-related attributes from the data. While it seems plausible, this information could be redundant to existing features of the data.

Discrimination occurs when a preset metric for fairness varies significantly across different subsets of the population. This is very problematic because the discrimination is due to class membership, rather than individual merits. It can have either a positive or negative context. Positive discrimination is favoritism that is shown to a subset of the population, e.g. affirmative action. While negative discrimination is when a subset of the population is marginalized, e.g. racism. Conventional wisdom would suggest that providing preferential treatment may guarantee fairness. However, a [paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1610.02413.pdf) suggests that it may even exacerbate inequality.

There are two major classes of models in machine learning that include discriminative models and generative models. A discriminative classifier is meant to discriminate data points by conditioning the labels on the input, whereas the generative model models the joint distribution between the input and labels. The model has to decide on a set of given data. It should be known that a classifier is only fair to every class in the data. This is given that there is no significant difference in metric for estimating fairness across the classes in the data set.

At this point, we would like to figure out the connection between uncertainty and fairness. Uncertainty modeling is a method of explaining aspects of the unknown unknowns of our model. This is the ability to figure out the information content of the blind spot of a machine learning model. Even with the most sincere of intentions, unfairness can occur, as it can manifest itself as a blind spot in our algorithm. Aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty are the two common types of uncertainty in Bayesian statistics. Aleatoric uncertainty occurs due to noise in the observation, which could be estimated by modeling the noise distribution. Epistemic uncertainty arises due to missing data which could be estimated by imposing a prior distribution over the parameters of the model. This could be done by monitoring the effect of change as the data is varied. [Aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1703.04977.pdf) were combined to learn noise attenuation, thereby improving the neural model. However, there is a caveat, since the noise may be applied uniformly to all the considered population, so our best efforts may not yield the intended results. Probabilistic numeric is another form of uncertainty due to computation, as described in the [paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1506.01326.pdf).

The question of how many samples can be estimated is a tricky proposition. This is because we are more likely to have a fairer model if the data is evenly distributed and similar to the probability distribution in the world. Therefore, the ideal fairness will be a perfectly balanced data set with equal proportions of subclasses. However, if the balanced subsets are not diverse and not similar to the world probability, then fairness may not be at the desired target. As regards handling unbalanced data, future advances would make feasible the ability to learn from a few examples per class using single-shot learning. There are a few open questions that still need to be answered with regard to sample size. How many additional data points per subpopulation does one need to improve the fairness of a classifier among the various subpopulations? We would have to borrow ideas from the [paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1805.07883.pdf) that sets bounds on sample complexity, and then adapt the system for fairness. A more intuitive question would be to model fairness as a parameter and optimize for it in the loss function as described in [paper](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1803.04383.pdf) where fairness is defined in the regularization scheme.

#### Evaluation

Fairness can be considered at an individual or group level. This provides a realistic way to estimate fairness in a population.

##### Individual level metric

Consistency score is used in literature for measuring the relationship between an object in cluster analysis. It can also be used for estimating fairness in our context.

[Consistency score](http://www.francescobonchi.com/KDD2016_Tutorial_Part1&2_web.pdf), $\text{C}$, is a measure that determines if similar objects in the population share similar outcomes. This measures fairness at an individual level.

$$

\text{C}=1-\sum_{i} \sum_{y_{j}\in \text{knn}(y_{i})} |y_{i}-y_{j}|

$$

where $\text{knn}(y_{i})$ is the k nearest neighbors of $y_{i}$

The metric uses the nearest neighbour to each instance of the population and obtains a summation of absolute error between each instance and its nearest neighbours. This has the limitation of setting the number of nearest neighbours as a hyperparameter. Due to this, the metric is quite subjective to the value of the nearest neighbours that were selected. [KNN](http://www.cs.haifa.ac.il/~rita/ml_course/lectures/KNN.pdf) gives us the ability to capture the characteristics of multi-modal distributions. The rule of thumb for choosing the $K$ in KNN is the $K$ should be large enough to minimize error and small enough to capture locality information.

##### Group-level metric

The measure of discrimination in comparison between the protected group and unprotected group. This involves quantifying fairness at the level of their membership in different subsets of the population. This gives the average or global measure of the effect.

| group | denied | granted | |

| :--- | :----: | :----: | ---: |

| $protected$ | $a$ | $b$ | $n_{1}$ |

| $unprotected$ | $c$ | $d$ | $n_{2}$ |

| | $m_{1}$ | $m_{2}$ | $n$

Table 1: Benefits (denied vs granted).

$p_{1} = a/n_{1}$, $p_{2} = c/n_{2}$, and $p = m_{1}/n$ respectively.

Risk difference, $\mathrm{RD} = p_{1} - p_{2}$

Risk ratio or relative risk, $\mathrm{RR} = \frac{ p_{1} }{ p_{2} }$

Relative chance, $\mathrm{RC} = \frac{ 1-p_{1} }{ 1-p_{2} }$

Odds ratio = $\frac{ RR }{ RC }$

Risk difference can be used to estimate the difference between the probability of an outcome between the protected and unprotected groups of the population. For example, in our table, the proportion of the protected population getting denied should be similar to the proportion of the unprotected subset of the population. This can be extended to the population with multiple classes. This is done by comparing the proportion of a class of the population to the absolute value of the average of the proportions per class.

Risk ratio, RR is the ratio of the probability of an outcome in the protected group in comparison to the probability of the same outcome in the unprotected group.

| Score | Interpretation |

|----------|-------------:|

|RR=1 | no discrimination between the protected and unprotected groups in the population. |

|RR<1 | protected group is negatively discriminated (punished) against in the population. |

|RR>1 | protected group is positively discriminated (favored) against in the population. |

Table 2: Interpreting the value of the Risk ratio.

Relative Chance, RC is the ratio of the probability of an outcome not occurring in the protected group in comparison to the probability of the same outcome not occurring in the unprotected group.

| Score | Interpretation |

|----------|-------------:|

|RC=1 | no discrimination between the protected and unprotected groups in the population. |

|RC<1 | protected group is positively discriminated (favored) against in the population. |

|RC>1 | protected group is negatively discriminated (punished) against in the population. |

Table 3: Interpreting the value of Relative chance

Odd is the likelihood that an event will or will not occur. Odds are not the same as probability. For example, odds for 2:1 are equivalent to a probability of $\frac{2}{3}$.

Odd ratio, OR is the ratio of the odds of an outcome in the protected group in comparison to the odd of the same outcome in the unprotected group.

| Score | Interpretation |

|----------|-------------:|

|OR=1 | no discrimination between the protected and unprotected groups in the population. |

|OR<1 | protected group is negatively discriminated (punished) against in the population. |

|OR>1 | protected group is positively discriminated (favored) against in the population. |

Table 4: Interpreting the value of Odd ratio.

There are metrics like area under a curve (AUC) and F-score among others. However, these metrics would need to be tuned by altering the thresholds to guarantee certain target values for fairness across different subgroups.

### Adversarial attacks

Machine learning models can be vulnerable to carefully crafted examples designed to fool them. The art of designing countermeasures to enhance the robustness of the model. One school of thought is to treat adversarial attacks as a security threat. However, another school of thought is to treat adversarial attacks as a means of improving the robustness of the model.

The consideration for handling adversarial examples must be shaped by business needs as defenses against adversarial attacks can lead to performance degradation and could also lead to loss of intellectual property as shown in the work on [stealing the model](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1609.02943.pdf) served as a web service. The trade-off between performance and stability should be factored in to reach a well-informed decision.

There are several [attack strategies](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.00069.pdf) that can be used to stage an [adversarial attack](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.00069.pdf). It is a poisoning attack that leads to contamination of the training set, thereby compromising the learning algorithm. An evasive attack occurs by modifying the testing examples to confuse the system. The settings do not influence the training phase of the model, and an exploratory attack requires black-box access to the model by gaining more information about the system and identifying patterns in the training data.

Adversarial attacks can be categorized into white-box and black-box attacks. In the white-box setting, the attacker knows the parameters of the model. The attack strategy is based on the gradients with respect to the loss function. This is analogous to a chosen-plaintext attack in cryptography. By carefully passing a data set through the model and getting predicted labels. Whereas in the black-box setting, the attacker estimates the parameter of the model by observing the behavior of the network on some carefully made inputs. The attack strategy is based on an approximation of the gradient with respect to observed changes in the input.

There are several defenses against targeted adversarial attacks. However, there is no universal defense for every adversarial attack. Adversarial defenses can prevent a model from compromising the data on which it was trained. Defense can include data augmentation with original and perturbed data. The technique of distillation has been proposed to protect from adversarial attacks with some loss in performance.

### Connecting the dots

Fairness can be similar to an adversarial attack. The degree of fairness quantifies the level of discrimination, whether it is intentional or not. Adversarial attacks are usually carefully crafted. However, making the classifier robust to adversarial attacks results in increased gains in addressing edge cases or blind spots in the model. Fairness is built into the model rather than as an afterthought after building the model. Incorporating fairness in the model can lead to creating more robust models.

The current advances in neural computation are limited in scope for safety-critical systems such as self-driving cars operating at level 5. This motivated the need to ensure neural networks are robust to adversarial examples while keeping fairness at an acceptable level. Several remedies have been suggested in the literature for handling adversarial attacks, including augmentations (with a set of transformations), distillation ( for knowledge transfer between models), and many ensemble models to mitigate against adversarial attacks. A known limitation in existing countermeasures for adversarial attacks is the inability to generalize to miscellaneous scenarios. The adversarial attack could be in the form of corrupting the data by perturbations and thereby biasing the learning algorithm. One possible direction of research is to develop generic countermeasures suitable for computer vision in adversarial settings, which is a step beyond handcrafted [adversarial attacks](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.00069.pdf).

Adversarial attacks can be thought of as a classifier that is unfair in some classes, which can include the subset of the data that has the adversarial examples. I think the discrimination is not really against the adversarial examples, but against certain subgroups of the population, of which the examples are representative. However, an unverified school of thought can assume that the classifier is biased against the adversarial examples. Hence, the weak relationship between fairness and adversarial attacks.

Fairness should be considered from the data collection stage of the processing pipeline. Trying to get a stratified sample of the population. You should gather more data in the form of active learning if a class of data has an unacceptable measure of fairness and rebuild your model.

### Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Dr. Ziyuan Gao and Dr. Eugene Yablonsky from the National University of Singapore and Fraser Valley University, BC respectively. They provided technical support during the writing of this manuscript. I am grateful to the advanced reading group under the umbrella of [Learn Data Science meetup](https://www.meetup.com/LearnDataScience/) in Vancouver for the lively intellectual conversations on several machine learning topics.

### Recommended Readings

Here are some of the materials that gave me a mental model of the problem.

##### Tutorial

- https://www.slideshare.net/KrishnaramKenthapadi/fairnessaware-machine-learning-practical-challenges-and-lessons-learned-wsdm-2019-tutorial

- http://www.francescobonchi.com/KDD2016_Tutorial_Part1&2_web.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIXIuYdnyyk

- https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1D7hjxWgv8wYFBAaGIHRu-pW_hq2niFee2me9tfAAg3g/edit#slide=id.g3bfee62da5_0_0

- https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Zseg5dEBFL1Z2emoDFL8TDsnrLvzC2kF/view

- https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rUQkVS0NzSH3IEqZDsczSxBbhYHbjamN/view

##### Paper

- https://5harad.com/papers/fair-ml.pdf

- https://5harad.com/papers/fairness.pdf

- https://5harad.com/papers/threshold-test.pdf

- http://delivery.acm.org/10.1145/3290000/3287589/p329-Friedler.pdf?ip=174.6.67.20&id=3287589&acc=OPEN&key=4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E6D218144511F3437&__acm__=1551158038_937b36cc03df8cdc9f386f13c9ba662c

- http://www.jmlr.org/papers/volume18/17-514/17-514.pdf

##### News articles

- https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/20/upshot/algorithms-bail-criminal-justice-system.html

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/10/17/can-an-algorithm-be-racist-our-analysis-is-more-cautious-than-propublicas/?utm_term=.ad9d95b2cd5e

##### Algorithm bias

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2886526

- https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.06705

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1712.07107.pdf

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.05666.pdf

17/18

Please feel free to donate to support my work by clicking